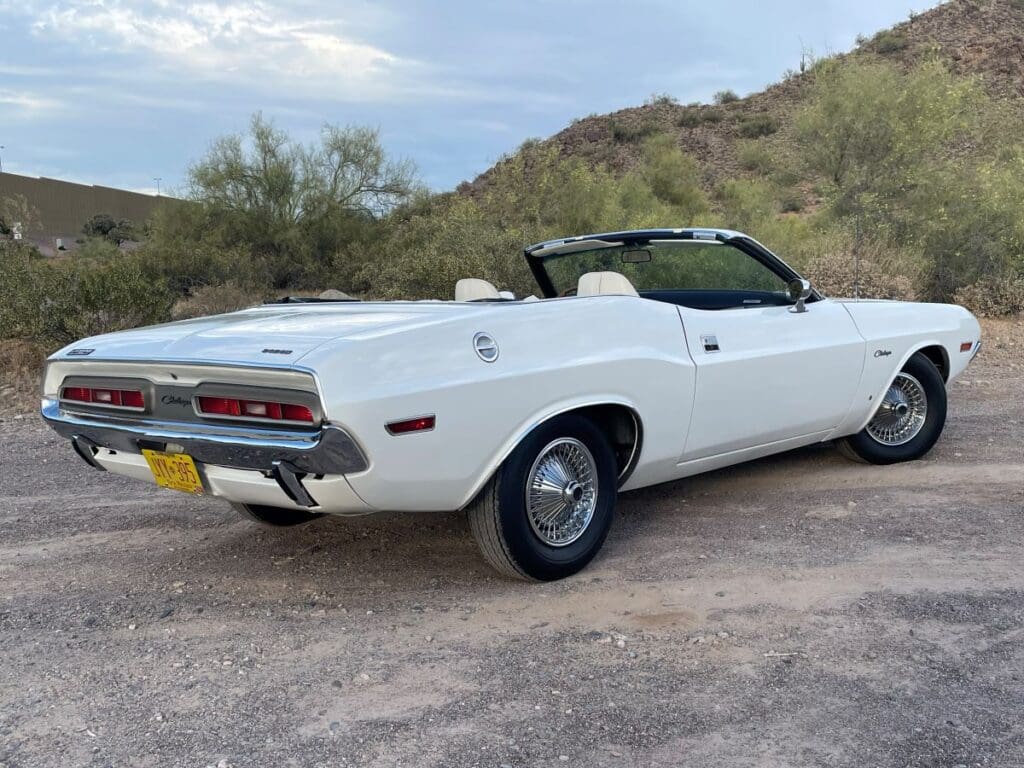

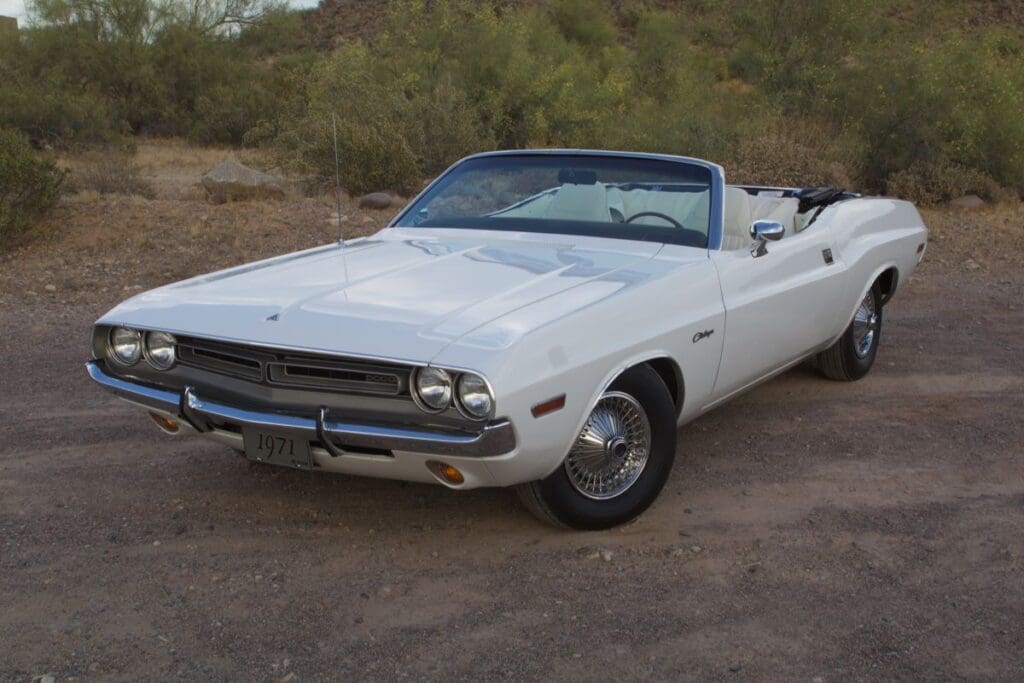

How many owners would be tempted to take a plain Jane Challenger and transform it into a fire-breathing, big cube muscle car tribute? Not this owner, who chose to restore his one-family owned, one-of-122, 383/2bbl 1971 Dodge Challenger convertible to how it left the factory…

Words and photography: Jeff Koch

The term ‘restoration’ has been badly abused over time. A restoration is generally bringing an item back to new, using original, or identical-to-original components. A simple paint job, whether in the car’s original colour or your favourite shade of sky-blue pink, is not a restoration – it’s a refresh. Pulling an ailing, wheezing Six and dropping four-hundred-odd cubic inches of sheer throbbing power between the shock towers is not a restoration – it’s building a hot rod. Slapping a star on the door and lights on the roof of your favourite American sedan is not a restoration – it’s a cliche. Restoration, making it as it once was, is a far more restrictive thing. And doing it right is neither easy nor cheap.

Enjoy more Classic American reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Pure restoration tends to happen to the most desirable cars. Alas, rarity and desirability don’t always run parallel. This car is a perfect example. Stats showed that just 122 two-barrel 383-powered Challenger convertibles were shoved out the door at Hamtramck Assembly in 1971. There were more Challengers with bigger engines, more attractive equipment, built in larger numbers than this. But who’s clamouring to restore a 383/2bbl Challenger? Why, Jason Sada is.

Having just graduated, with a young and growing family at home, Dr Farid Sada thought he’d treat himself. The freshly minted doctor of internal medicine, who was just wrapping up his residency in Albuquerque, marched into Dodge Country, Inc., in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and ordered the car of his dreams. Along with the unusual engine choice (which mandated the three-speed TorqueFlite automatic transmission), this Challenger was painted Brite White, with a white bucket seat interior, and featured air conditioning, power-steering, power front disc-brakes, AM/FM stereo radio, console, chrome door mirror, and more. These elevated the $3207 Challenger to $4641 as it appeared on the spec sheet.

It was Dr Sada’s everyday driver for a decade and a half, until he handed it down to his son, Jason – who proceeded to pile on the miles for another decade. You hear tales of cars going rotten in just a couple of years, but in the desert Southwest this isn’t the case: rust is virtually unknown there, unless the sun bakes through the paint and exposes bare metal to the atmosphere. After a quarter-century of more-or-less faithful service, Jason parked it up and forgot it. However, a chance meeting at a local filling station kick-started the current owner’s impetus to restore. Ward Gappa, owner and proprietor of Quality Muscle Car Restorations, in Scottsdale, Arizona (www.qualitymusclecarrestorations.com), picks it up from here. “In February 2017, I was at a Safeway gas station in Mesa, filling up a customer’s black 1970 Cuda 440 Six-Pak when Jason approached me. He told me about his original-owner 1971 Dodge Challenger convertible in need of a full restoration.” Soon, Ward was sussing out what needed to be done. The short answer: everything needed to be done.

A new life beckons

Dormant since the mid-1990s and having been shuffled around from storage units over the next couple of decades, the Challenger was complete but needed to be gone through. The hood and trunk needed metal work, a result of heavy objects laying across the car while in storage. Both valances and one rocker panel had kerb damage. Parking lot rash appeared up and down both sides, while a poorly executed 40-year-old repair showed itself on the passenger’s-side rear quarter. Inside was worn, but surprisingly clean, with only the door panels and dashpad out of sorts. There are ample amounts of reproduction parts available for any E-body these days, but Ward’s path was clear: restore and reuse as many factory components as possible, source others if the original materials were too far gone and be true to how the car was originally built.

The engine was a replacement 1969-era 383, installed decades previously. Chrysler Corporation’s low-compression ’69 383 two-barrel offered an advertised 290 gross horsepower with 9.2:1 compression; the original ’71 engine had lower 8.5:1 compression and was rated at 275 gross horsepower (190 net). It’s got a bit more now: the engine was disassembled, hot-tanked, Magnafluxed and cleaned, before the block was bored .040-over. The block was line-honed and the deck was squared. The cylinder heads were treated to a mild port job to help airflow, and the exhaust manifolds were milled to properly seal to the heads. The valves received a three-angle cut, with hardened exhaust valve seats installed to accommodate modern fuels. There’s easily an honest 300 gross horsepower at work now.

The transmission isn’t matching-numbers either: it was a 1972-era 727 three-speed automatic that likely was swapped in at the same time as the engine and was rebuilt. Other than the driveshaft U-joints, and a sketchy replacement single-exhaust system, all of the original components were pulled, inspected, refinished and reinstalled. A Waldron Exhaust true-dual system was also installed, to relieve some backpressure. Hoses and rubber bushings had dried out and needed replacing with like-for-like items, brake rotors were machined, the drums were relined, and new parts-store-sourced calipers replaced items ruined by fluid from burst hoses; otherwise, the bulk of the chassis was cleaned and reused.

The body was largely as good as you’d hope a Southwestern car to be, save for the poor passenger’s-side repair, and the rusty rear quarter on the driver’s side. That quarter was a bit of a surprise, though Jason absolutely believes that moving around dry climates (only New Mexico and Arizona its whole life) saved his Challenger from deteriorating further. Once the dents were pulled, and the rust was repaired, the body received a filler skimcoat, a couple of rounds of prime-and-sand, and eventually PPG two-stage paint used as a topcoat, which was then colour-sanded, buffed and polished to an as-new shine. All of the original side glass was reused, although a correctly date-coded windscreen was sourced from ECS Automotive Concepts in Missouri. Exterior brightwork was all cleaned, polished and reused – even the mounting hardware is factory original.

The interior was stripped to steel, and it was quickly determined that, save for the dash pad, seating surfaces, door panels, carpet and glove box liner (hacked up to install an aftermarket radio), practically everything else could receive a simple cleaning and polishing before being reinstalled. A generous quantity of Dynamat Xtreme Bulk insulation sheets, a modern material vastly superior to older rubber- or jute-based solutions to keep noise and heat out of the cabin, was installed on the Challenger’s floor, before a moulded black carpet was installed atop it. Seats were refoamed by Joe Reece of Cottonwood, Arizona, and installed at the same time as the Legendary Auto Interiors (www.legendaryautointeriors.com) seat covers. A new reproduction convertible top was sourced, as were hydraulic lines to electrically raise and lower the roof at the touch of a button; but the bulk of the rest, from motors to wiring to weather-stripping, was cleaned and reused.

Now, as we all know, the Challenger had a variety of hot versions in its first couple of years – 340s with four- or six-barrel carbs, four barrels of carburetion atop that 383, a torquey 440, and even Hemi power could have been sourced to rest in that K-frame. That flat hood could have been swapped for one with moulded-in scoops, or else a big pentagonal hole for a Shaker scoop. The trunk lid could easily have sprouted a wing on pedestals. Hubcaps could have been replaced with Rallye wheels – an easy bolt-on that would allow for wider tyres. The interior could have quietly received a gauge package or other options. And in lieu of clinical white, any number of more outrageous High Impact colours could have covered the Challenger’s comely flanks – Panther Pink! Plum Crazy! Citron Yella! Top Banana! Jason’s sons, ages 19 and 17, would be able to tool around in something with arguably a lot more eyeballs on it.

But then, with a hot paint colour, spoilers, scoops, and more power … it wouldn’t be the same car, would it? It wouldn’t be the ride Dr Sada bought in Albuquerque after he finished off his med school. It wouldn’t be the car that Jason grew up in. It wouldn’t have been the machine that Jason piloted for another decade after. It wouldn’t be true to what it was; it would be something else entirely. To his credit, Jason didn’t even think about making his family’s Challenger into something else. A secret Hemi homage was never in his head. “Honestly, I’ve never been a car collector… and so I’ve never had the desire to put much more into it than what it came with from the factory,” Jason said. “I just want to keep it the way it was.” Indeed, these days it’s a lot harder to find a 383/2bbl car than it is a Hemi or 440 around southern Arizona – and Jason uses the car of his father’s dreams recreationally, on the weekends, to conjure up memories of his dad and his own years growing up in the back seat (and later behind the wheel). A restoration did that; a fist full of modifications couldn’t. Not in the same way. Ironically, in a dying era of deep-breathing tyre-frying muscle cars, the idea that this ’71 Challenger convertible has remained true to what it always has been, and hasn’t been turned into something else, is as refreshing as a top-down desert cruise at dusk.

By The Numbers

Dodge’s Challenger came hot out of the gate for 1970, but with the end of the muscle car era rapidly approaching (and the car buying public seemingly understanding this), the model’s outlook for 1971 was considerably less rosy. Just 29,883 ’71 Challengers of all flavours were sold for the model year, a 64% drop from 1970. No convertibles were photographed for the ’71 Challenger sales brochure, with the only ragtop appearing an illustration of a purple model.

Yet somehow Challenger’s convertible sold better (or perhaps more correctly, less badly) than the average Challenger that year: with 2165 sold including Canadian and export orders (and just 1793 if you only count sales in the States), soft-top sales dropped only 31.8% year-on-year. As Chrysler looked to save money by minimising the number of body styles it had to build, the E-body convertible disappeared at the end of the ’71 season (despite what American TV programming like Mannixand The Brady Bunch might otherwise suggest). Records suggest that, in 1971, Dodge built a total of 122 383/2bbl-equipped Challenger convertibles. How many are left today?